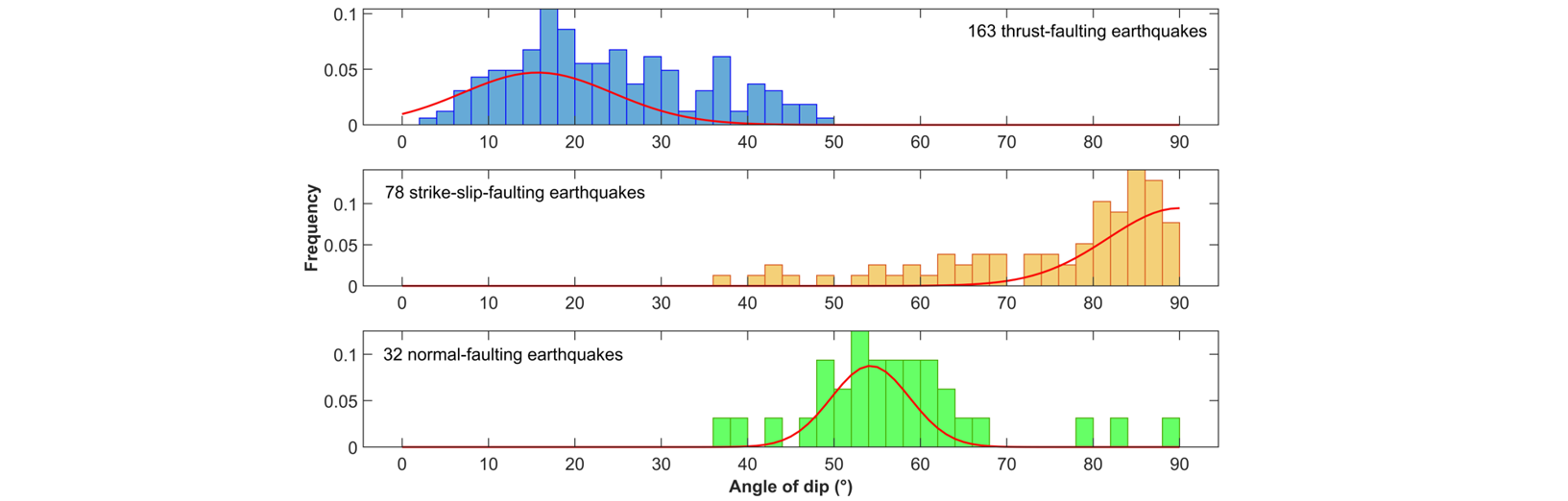

In the brittle regime, faults tend to be oriented along an angle of about 30 relative to the principal stress direction. This empirical Andersonian observation is usually explained by the orientation of the stress tensor and the slope of the yield envelope defined by the Mohr-Coulomb criterion, often called critical-stress theory, assuming frictional properties of the crustal rocks (μ ≈ 0.6-0.8). However, why the slope has a given value? We suggest that the slope dip is constrained by the occurrence of the largest shear stress gradient along that inclination. High homogeneous shear stress, i.e., without gradients, may generate aseismic creep as for example in flat decollements, both along thrusts and low angle normal faults, whereas along ramps larger shear stress gradients determine higher energy accumulation and stick-slip behaviour with larger sudden seismic energy release. Further variability of the angle is due to variations of the internal friction and of the Poisson ratio, being related to different lithologies, anisotropies and pre-existing fractures and faults. Misaligned faults are justified to occur due to the local weaknesses in the crustal volume; however, having lower stress gradients along dip than the optimally-oriented ones, they have higher probability of being associated with lower seismogenic potential or even aseismic behavior.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772883823000341